It was 6 a.m. on an unseasonably warm, humid November day as I waited for the white van I knew was due to arrive sometime before 7:30 a.m. I stood outside New Haven’s police headquarters, across the street from the train station at the corner of West Water Street and Union Avenue. The van was coming from York Correctional Institution in Niantic, Connecticut, a prison 45 minutes away. Inside the van there would be women who, when not in prison, live in the New Haven area. Other than that, I knew nothing about them. So I stood outside the police station, a brutalist, brown brick structure that takes up an entire block, and waited, passing time by marching up and down the section of West Water Street where I had been told the van would unload. A few people walked by, heading toward the train station, and police officers pulled into the parking lot across the street, reporting for work. Some of them eyed me suspiciously through their windows, but apparently decided that a 20-something Yale student, a white woman with a JanSport and a notebook, did not pose a threat. I could hear seagulls and the occasional train whistle. They sounded like they belonged to a different, more vivid landscape.

Just before 6:30 a.m., a big white vehicle came trundling around the bend that links State Street to Union Avenue. It turned onto West Water Street and stopped outside the police headquarters, about half a block from the corner. The vehicle had no windows, and it was bigger than I had expected, more like a high-security school bus than a van. For a few moments, nothing happened. Two officers, a man and a woman in grey uniforms, came out of the police station to my left and walked into the van. A second man got off the van and carried what looked like a plastic bag filled with trash into the building. A few more moments passed. Then a woman walked into view on the side of the truck opposite the prison — without hand restraints, and with two full plastic bags. She was short, maybe a little over five feet tall, bending sideways under the weight and volume of her bags. Her skin was light brown and her reddish-brown hair was straight and pinned up on her head in no particular style. She wore grey sweatpants, a grey long-sleeved shirt, a white T-shirt and laceless white sneakers. She walked toward Union Avenue, toward me, in the middle of the street.

—

A week earlier I had stood at the same spot, and instead of watching a single woman walk towards me, I had watched 12 women march from the white van to the jail — no one was going home. I had never witnessed anything like it: the state exerting its power over so many bodies that roughly resembled my own.

The scene plays out every single morning, except for weekends and holidays, at just this spot, in just this way, though the number of prisoners varies. It is one tiny window into the vast, shadowy world that is the American criminal justice system, a world that has expanded to grotesque proportions in the last 30 years. In 1980, well under 400,000 Americans were incarcerated. In 2013, 1.5 million Americans were in state or federal prison, and an additional 700,000 were in local jails. The number of Americans in prison is greater than the populations of 14 states.

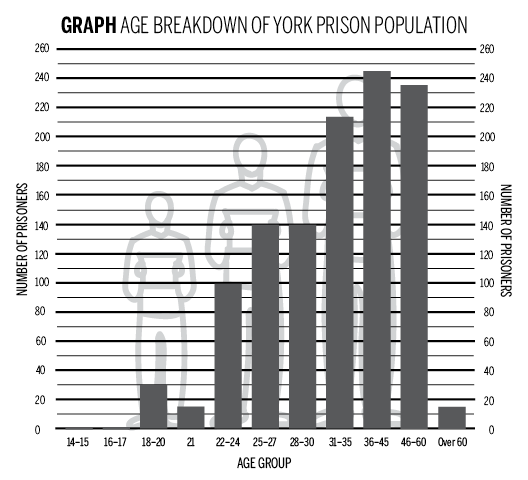

But beyond those numbers, there’s one I found most startling: From 1980 to 2010, the number of women in prison increased by 646 percent, a rate 1.5 times higher than the increase in the number of men in prison. The number of women in prison is still much smaller than the number of men; in Connecticut, women comprise only about 8 percent of the prison population. But from 1990 to 2014, the number of women incarcerated in the state increased some 87 percent to 1,084, while the number of men rose 66 percent to 14,941. The 12 women in the van were members of a metastasizing sorority.

When I used to conjure a prison in my mind, it was filled with men, a stereotype that is supported by the actual numbers and enforced by pop culture depictions of crime and criminality on television and in movies (with the obvious exception of “Orange is the New Black”). “The bad guy” is almost always just that: a bad guy. And while I knew enough about the racial and socioeconomic injustices of the criminal justice system to know that “the bad guy” is not always, or even usually, “bad,” I had not overcome the tendency to assume incarceration was a male story.

After the women disappeared into the building, I went to the public entrance of the police headquarters and asked the officer on duty where they were going. He told me that later that day, transport vehicles would arrive to take them to courthouses all over New Haven County. There they would wait, sometimes all day, to find out if their sentences might be reduced or lightened to parole, or if they might be sent to a different facility. At the end of the day, they would return to the Union Avenue jail, and then get back on the white truck with no windows for the drive back to York.

Someday, though, maybe in three weeks or maybe in 15 years, each of the women would leave the white truck and step onto West Water Street, without hand restraints and with two plastic bags filled with her possessions, unless family or friends could make the drive up to Niantic to pick her up there. Someday, the women would return home to New Haven, to a world transformed by the passage of time and the harsh reality of their criminal record.

—

The woman didn’t look back at the van to watch the other women make their way into the jail.

“Oh, my god,” she said to no one in particular. She was craning her neck toward the parking lot, searching desperately for someone or something. It looked like she might have started running if not for the bags she had to carry.

I got the feeling I was witnessing one of the most profound and disorienting moments in the woman’s life. She had been in prison for however long and now, suddenly, here she was — free. But freedom must have been disappointing: an unremarkable city block, with traffic picking up, nowhere to sit and no restaurants or other potential shelter visible. I wanted to talk to her, partly because I had the urge to offer her help, and partly because I was consumed by a voyeuristic curiosity, which made me uneasy. I thought that if I were she I would want to be left alone. But then we had made eye contact, and I heard myself saying hello, and I heard her say hi, and then I was introducing myself and asking how she was doing.

“Fine,” she said, still looking around.

I asked if she’d be interested in talking about how she was feeling.

“Uh, confused,” she said. “I’m looking for my ride. Could you just walk with me? I don’t know where he’s at.”

Together we walked to the corner and looked out towards the train tracks across Union Avenue. She asked me what time it was.

“6:39.”

“Oh, he’s not here then. He’s not coming until 7. So I guess we can talk right here.”

I was painfully aware that I had no idea how it felt to be her. I asked her what her name was — she told me Sharlice — and then what she was hoping to do that morning.

“I just had a baby,” she said. “So I’m just waiting to see him right now. I’m gonna see him, hopefully hug him and kiss him and cuddle him.”

Seeing my look of confusion, she explained further. She had been pregnant when she went in eight months earlier and she spent almost the entire pregnancy at York. When her son was born in September, her family drove up to be with her at the hospital but were not allowed by her side during the delivery. She spent two days with her newborn. Then the baby went home to New Haven with his father, her boyfriend James, and she went back to prison.

Sharlice told almost no one she was going to prison. She told everyone she was on a long vacation in Florida, where she has some family. Her best friend even bolstered the story, posting things on her Facebook wall like, “How’s Florida going?” Prison is embarrassing, and she didn’t want anyone to know she was there.

And it wasn’t her fault she was there, exactly, she said. She told me she had been arrested a few times for gang-related crimes and sentenced in 2013 to 18 months on probation. In the fall of 2014, while she was on probation, she was visiting a friend when they got into an argument. He locked himself in a room with her cell phone, and she couldn’t leave without getting her phone. She kicked the door in, grabbed her phone and was about to leave, but then she realized that her friend was having an asthma attack. She called 911, and when the ambulance arrived, her friend, delirious, told the first responders about someone “breaking and entering.” They called the police. When the dust had settled it was clear that she was not, in fact, a would-be thief, but was in violation of the terms of her probation. She told me that when she got arrested for the false “breaking and entering” charge, that counted as an automatic violation and got her jail time.

I didn’t understand how probation worked, exactly, so I asked her: Couldn’t your friend have told the police you weren’t really breaking and entering? She said he didn’t, or if he did, it didn’t do any good.

(Later, still puzzled, I called the New Haven Public Defender’s Office to ask about automatic violations of probation. An attorney named David Forsythe looked up Sharlice’s complete criminal record: charges all over the state since 2005, for things like threatening and breach of peace and assault, a year of jail for one offense, two years for another, 60 days for another. The recent prison sentence came after her fourth violation of the same probation. The court had previously issued a protective order to prevent her from contacting the friend who had an asthma attack, so simply being at his home was a violation of her probation. Forsythe told me a story about an intern he once worked with, who asked a client how many DUI offenses he had. The client said one, and the intern didn’t realize she had been lied to until she stood up in court and gave the judge demonstrably false information. “She said, ‘He lied to me! He lied to me!’” Forsythe chuckled. “I said, ‘Well, get used to it.’ Dishonesty among our clients is not terribly unusual.” I didn’t mind that Sharlice didn’t tell me everything. She didn’t owe me anything.)

Regardless, after the probation violation, Sharlice went back to York.

“Unfortunately, a part of me kind of regrets calling the ambulance for him,” she said. “My mom said it was the right thing to do, call the ambulance, because if he had died, I would have felt bad. But I said I never would have went to jail if I hadn’t been there.”

Sharlice, who is 27, grew up in New Haven and attended Wilbur Cross High School. Telling me this, she realized the risk of seeing someone she knew was not exactly small — a high school classmate or childhood friend could walk by on their way to the train station. The location, her outfit and the two bags of jumbled belongings made it obvious where she’d been. She asked to borrow my phone to call James, who was supposed to come pick her up. I handed her the phone, but she asked me to dial because it’d been months and she couldn’t remember how to use the touch screen.

She smiled when she heard his voice, but as the conversation went on, her face fell. I couldn’t hear James, but from what I could make out, he said the Connecticut Department of Correction told him she wouldn’t be in the city until 8:30 a.m., and he was busy getting the children ready for school and daycare. He said give him 20 minutes.

She handed the phone back. She said she could hear her son, Jamari, crying in the background.

“I feel so uncomfortable standing here,” she said. “I feel like a prostitute or something.”

Besides that, it was cold, and she didn’t have a coat. (When it gets really cold, officers at the Union Avenue building told me, the women will get dropped off and then haul their stuff around to the front of the building, where there is a door that leads to a small public waiting area in which they can make phone calls. The waiting area is about the size of a public restroom stall, but with no right angles. The tile floor is dirty and the space is claustrophobic. There are no chairs.)

Sharlice didn’t have any other clothes in her two bags. They were filled with a pillow, a breast pump she used to feed her son while she couldn’t be with him, pictures, she thought maybe a little bit of coffee, and she hoped her glasses, which might have gotten lost or broken as she packed up to leave York. She left her winter coat at her mom’s house. About every five minutes, Sharlice asked me if it had been 20 minutes yet.

When it had been, she called her boyfriend back and discovered he hadn’t yet left the house. He had asked a friend who lived nearby to come pick her up. Sharlice asked how the friend was supposed to recognize her.

“You would say pretty,” she said, smiling. “Well I’m not the only pretty girl outside of Union. I’m using the girl’s phone.”

Sharlice hung up again and we decided to walk farther down Union Avenue to the main entrance of the police headquarters, where she’d have a better chance of being seen. We looked through the windshield of every car that passed by, trying to find a driver who seemed to be trying to find us. And then she appeared, driving a beat-up silver Nissan with a big dent that looked like the result of a recent accident. She honked the horn a few times, short and staccato, and got out of the car. She was a very tall, very thin woman with shoulder-length straight hair and a big smile, wearing pajama bottoms and a tank top. She apologized for the way she was dressed — she was getting her son ready for school when she got the call and had to rush out as fast as possible, because she knew Sharlice must be anxious. She whisked Sharlice’s things into the backseat and Sharlice climbed in the front. I waved as the Nissan pulled away.

I was alone again, and the latest of the roughly eight women who return to New Haven from prison every month had gone home.

—

Home, as in the city of New Haven and the United States of America, is a place that does not quite know what to do with Sharlice, both because our society is only in the early stages of figuring out that a criminal record should not mean a life sentence of stigma, and because she is a woman who has done time in a world of re-entry services geared towards men. Where re-entry resources do exist, they’re limited — so limited that the Department of Correction did not put Sharlice in touch with a social worker or re-entry service provider, even though she had been in trouble with the law before and would seem to be a potential reoffender. When I asked her, she said she hadn’t received a list of nonprofits she could visit for assistance buying food and clothes, updating her resume and getting a free check-up. I was surprised to hear that, because I had accessed such a list online — the city’s “Reentry Resource Guide,” last updated in 2012 and thus imperfect, but certainly useful for finding essential services. I assumed the Department of Correction would print a copy for each person returning to New Haven.

I was also surprised that Sharlice had no contact at all with any re-entry counselors or social workers, because I knew that now, relative to the past, is a pretty good time to come home to New Haven from prison. The city’s re-entry assistance program, Project Fresh Start, just received a $1 million Second Chance Act demonstration grant from the federal Department of Justice and is aiming to cut recidivism in half among offenders aged 18 to 24. Project Fresh Start’s work is strongly supported by Mayor Toni Harp, who made re-entry a priority early on during her tenure. She renamed the “New Haven Prison Reentry Initiative” to the brighter-sounding Fresh Start, and moved the organization’s office from the second floor of City Hall to the first, a small change that makes a difference. When new clients walk in for the first time, the office they’re looking for is just a few steps to the right, not a frustrating walk through an imposing and unfamiliar building owned by the government they know best as the force that took away their autonomy. But Sharlice had never heard of Project Fresh Start.

In addition to Project Fresh Start, the city boasts a strong network of nonprofits that work with the re-entry population, from shelters to food banks to advocacy groups. Three of these organizations — Project MORE, Easter Seals Goodwill Industries and Community Action Agency — are community services that provide case-management programs, helping ex-offenders navigate their first 60 days to find housing and a job and plan for the future. These organizations are on the frontlines of the re-entry battle. Their caseworkers often pick people up at prisons or at the drop-off points in the city (Union Avenue for women, Whalley Jail for men), help move them into temporary housing and coach them through job interviews. They keep their phones on all night in case a client calls with a crisis.

An ex-offender can only access the potentially life-changing resources these organizations provide if he or she is referred to them by the Department of Correction. And that depends on a number of factors beyond the ex-offender’s control, such as whether their release date aligns with an opening for a new client at one of the programs, or whether they serve their entire sentence in prison or get released early on probation. According to Chance Bentley-Jackson, project manager at Project Fresh Start, the majority of people referred by the Department of Correction to the case-management programs are on probation because they were released early from prison for good behavior. The state can make completion of a re-entry program part of the requirements of the probation. But if someone serves their entire sentence in prison, like Sharlice, they are much less likely to get referred to a social worker because the state can’t require them to do anything. Bentley-Jackson called this a “broken system” because it allows so many people to slip through the cracks. But he added that if a prisoner actively pursues re-entry planning and spends time and energy finding out what resources are available, they can usually get some kind of help.

“In prison, I don’t feel like they expose everything to you,” Bentley-Jackson said. “Like if you want the information, you gotta go get it.”

Carlah Esdaile-Bragg, the director of community re-entry services at Easter Seals, said the unique problem women face is that there are so few of them that practically no services are dedicated to them alone. For example, Bentley-Jackson said approximately 60 percent of returning ex-offenders stay at a halfway house when they first come home to New Haven, regardless of whether they have been referred to a program. But there is no halfway house — not one — for women in the Elm City. They can choose between going to a house elsewhere in the state, or going right back home with little opportunity to think through the challenges they might encounter there. York offers child care classes, but little information about how to wage a legal fight for custody of one’s children after leaving jail. And Esdaile-Bragg said Easter Seals started its women’s support group only recently, and is still in the process of crafting the curriculum and making it well known in the community.

There are also smaller problems that underscore the degree to which re-entry is largely a man’s world — the hygiene supply closet at Family ReEntry, Inc., an agency that offers services for people who are out on parole, has men’s undershirts and socks, Axe deodorant and men’s razors clients can pick up when they come in for appointments with social workers. But caseworker Christie Huntley, who works with about 30 women a year (a tiny portion of the agency’s 650 clients) said the closet never has brands of soap and shampoo targeted to women, nor bras, tampons or pads.

The need everywhere is so enormous, Esdaile-Bragg said, that the re-entry service community has essentially practiced triage, focusing on the group most in need, which, in terms of size, is men.

If the status quo persists, the rising numbers of women returning to New Haven from prison will find themselves treated as an afterthought, thrust into programs that may have the resources to accommodate them but were not designed for them. For Sharlice, however, the gender sensitivity of re-entry resources is beside the point — New Haven’s programs might as well be in a different state. As Bentley-Jackson explained, this may be in part the result of Sharlice’s lack of initiative in prison. But it seems to me that the people least likely to seek re-entry assistance are the most likely to need it.

—

I had left Union Avenue feeling surprised about the difficulty and anxiety of even Sharlice’s very first moments back in New Haven. And part of that anxiety seemed inflected by gender: a man standing on the same street corner would likely feel less concerned about being mistaken for a prostitute, and would probably be less physically vulnerable if he decided to walk home on his own, heavy bags in tow. But there were other issues she faced right after stepping out of the white bus — somehow, her family had been told they didn’t need to pick her up until 8:30 a.m., even though the bus from Niantic always arrives before 7. And other than the street corner or a tiny, dirty room, there was no place for women to wait for their families.

Sharlice’s 45 minutes waiting on Union Avenue seemed to typify the re-entry experience for women writ large: It’s hard, and made harder by the reality that the system is not designed to think of ex-offenders as people who might have different needs based on their backgrounds, including gender. What might that mean for Sharlice as she continues the process of re-entry over the next few weeks, months and years? In some ways, her situation seemed positive: She had family in the area and a partner who has no criminal record — Esdaile-Bragg said relationships with men who have been incarcerated often contribute to women’s recidivism. And Sharlice had a high school diploma, which would help with the job search, and she would not need to fight to regain custody of her children from the state Department of Children and Families, which would save time and emotional energy. But I felt angry at the injustice that she had not been paired with a re-entry counselor or social worker in New Haven while she was still at York. As soon as she left the white truck, the Department of Correction was officially done with her, unless she got in trouble again.

—

Sharlice had been home for three weeks when I saw her next. We met at a Burger King in West Haven, down the street from the house she had just moved into with her boyfriend and kids. She wore red Minnie Mouse pajama bottoms, a white t-shirt and a grey hoodie. She carried a thermos of coffee and a plate of two biscuits with bacon and eggs — her sister had made breakfast. She showed me pictures of her children: her three-year-old daughter in a princess outfit at her birthday party last week; her son, now three months old, in a bib that reads “I have the coolest grandma!”

She was applying for jobs, so many she’d lost track. Her best friend was texting her job openings, and her boyfriend was pushing her to follow through with applications, which she found motivating but also overwhelming. She had interviews coming up at Walmart, McDonald’s and, tomorrow, Dunkin’ Donuts.

“Listen to this and tell me what you think,” she said, leaning forward across the table. Dunkin’ had asked her to come in at 7 a.m., and to bring her Social Security card and ID. “Do you think they’re going to hire me? My first thought is the reason they asked me to come that early is they wanted me to start the first shift.”

I didn’t know, but thought that sounded plausible. I asked her if her criminal record has made her job search harder. She said no — through the Work Opportunity Tax Credit, employers get a tax break for hiring ex-felons, so she’s found it fairly easy to get interviews. Still, the job search always takes time, and if she couldn’t get a job soon, she wouldn’t have money to buy her kids Christmas presents. That day, she was going to the West Haven Public Library right across the street to sign up for Toys for Tots.

She said the hardest part of coming home had been readjusting to taking care of her kids, all day, everyday. Her three-month-old was still waking up often throughout the night, and since she was in prison for the first eight weeks of his life, she needed time to get used to that. And he needed time to get used to her.

“He watches me when I go to the door,” she said. “I think I’m gaining his trust, that I’m not leaving him again. Once I left him in the hospital the first time, they’re like ‘You gotta re-bond and stuff. He knows you but he knows that you left, too.’ Which, I didn’t leave. I was in jail. I had to give birth to him and go right back.”

When I told my own mom about Sharlice’s pregnancy, she winced, as if it hurt just to contemplate the experience of being separated from your newborn child within 48 hours. But Sharlice’s pregnancy and delivery are not that unusual. In 2004, a survey by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 4 percent of women are pregnant when they arrive at state prisons. Enough women were pregnant at York while Sharlice was there that there was a special group for them. They read books about childcare and talked about their “situations,” as Sharlice calls it. That’s where she found out she was actually “a lucky one” because her son went home with his father, and he could visit her while she was at York. Many children were not picked up by relatives but were instead taken directly into state custody, and might never be seen by their mothers again.

When this happened, Sharlice said, the women turned to self-mutilation.

Separation so soon after birth is traumatic for mothers and infants alike. In response to this reality, 10 states have established a prison nursery program, where women can live with their infants behind bars for a year or two. Connecticut, with its single women’s prison, would seem to be an ideal location for a nursery program: One facility could dramatically alter the status quo in which women are removed from their children, and infants are taken from their mothers into the custody of the state or relatives who might be less dedicated caretakers. In 2014, “An Act Establishing a Child Nursery Facility at the Connecticut Correctional Institution, Niantic” passed the Connecticut House Judiciary Committee with support from the Office of the Public Defender, the Department of Correction and a host of nonprofits, academics and city officials. But the bill never came up for a floor vote, and it hasn’t been brought up in the 2015 session.

I asked Sharlice the question I had been pondering for weeks: Had being a woman changed her re-entry experience? A biological male could not give birth in prison, and so in at least one sense the generic male re-entry experience would differ from Sharlice’s, right? No, she said.

“I think we’re all the same when we get out,” she said. “People have good intentions of coming home and doing the right thing, but make bad choices.”

Sharlice distills the re-entry experience to its most universal terms: the hope of doing well, clouded by the ever-present possibility of heading down the wrong path. That does transcend gender. But in its particulars, it seems to me, re-entry in New Haven is not the same for men and women, from the first moments of freedom, to navigating the challenges and expectations of home life, to the risk of recidivism.

For her part, Sharlice has no expectation that any nonprofit or government service will come to her aid. So now she is trying on her own to stay away from old friends and out of jail. She spends most of her time with her kids and her boyfriend. While we talked at the Burger King, he was Facebook messaging her. She showed me pieces of their conversation from earlier on her phone: cute sayings like “I like when you smile but I love it when I am the reason,” and a long series of little figures doing dance moves, a few from her and then a few from him, over and over. Sometimes, Sharlice said, they sit in the same room and text each other.

But sometimes she gets tired of him. After an hour or so at the Burger King, he started asking if she was really with a woman doing an interview. Sharlice got irritated, saying we had to go stand on her porch so we can show her boyfriend she wasn’t lying.

We went outside and she lit a cigarette. It was a block or so to their house, on a street with boxy wooden homes that have front porches and two stories.

We went up the steps to their porch and she called her boyfriend. Apparently he could see us through the windows. I turned around and gave a little wave, not quite sure what to do. “Ha, did you just say, ‘I’m gonna watch you gals?’” she laughed into the phone. Then: “Yeah, that’s why she’s doing the study, she never had the perspective of girls in prison … ok, I’ll be in in a minute.”

She hung up and took another drag on her cigarette. We were looking out across the street, to the train tracks behind the houses on the other side. The Metro-North train comes through here dozens of times every day. Just a few more miles and the tracks run along Union Avenue and pass the police headquarters where we met three weeks earlier. A whistle blew, and a train passed.

“It’s really nice when you’re sitting in the dark and the train goes by like that,” she said. I nodded. I said good luck on the job interview tomorrow, goodbye, have a nice day. Sharlice went into her house, back to her life and the hope of living it long enough and well enough to make prison a place that doesn’t matter, like a Florida beach she visited a long time ago, or a place she’s never been.