The wooden stock is beige and battered with age. The metal plate above the trigger is decorated with a pair of birds. The barrel is long, heavy and octagonal.

It’s an old muzzleloading firearm, for sure. It might even be the one that killed the deer that gave Buckhead its curious name in 1838.

John Beach, president of the Buckhead Heritage Society, is still trying to figure that out, partly by tracking the tales surrounding another little-known piece of area history – an 1842 log cabin that quietly survived destruction by being moved to a Buckhead back yard. In the meantime, Beach gave the Reporter an exclusive close-up look at the recently rediscovered weapon nicknamed the “Buckhead Gun.”

“My belief is we’ll never prove it was the actual gun,” says Beach, taking a scientific stance about the potential deer-slaying artifact. He thinks that at best, historians could only prove it’s not the weapon that killed the Buckhead buck, if the age or ownership record turns out to be wrong. (As of yet, there’s not even expert opinion on whether it’s truly a gun – meaning a smooth internal barrel, as it appears at a non-expert glance – or a rifle, with a barrel grooved for accuracy and distance.)

But what is already known about how the firearm fits into Buckhead’s bloody legend is compelling.

The name is said to have originated in the public display of the head of a buck outside or close to a general store run by Henry Irby at the intersection of today’s Peachtree, Roswell and West Paces Ferry roads in what is now Buckhead Village. The building stood roughly where the Whole Foods supermarket is today, Beach said. The area was initially called Irbyville before the allure of the deer’s head took hold.

Heritage Society research found that the deer was shot not by Irby, as long thought, but rather by a neighbor named John Whitley or his unnamed wife. The display of the head may have been part of the common method of field-dressing a deer after a successful hunt – propping its severed head on a tree branch or stick, Beach says. Virtually all of that information lacks primary sources and has come down as oral history; one narrative suggests that the deer head was displayed across West Paces Ferry around what is now the St. Regis hotel.

Soon after, the Whitleys bought 40 acres of land in the Vinings area of nearby Cobb County – near today’s SunTrust Park — and in 1842 built a log cabin there, according to the Heritage Society. According to one newspaper article roughly a century later, John Whitley was killed by “rebellious slaves” shortly before the Civil War.

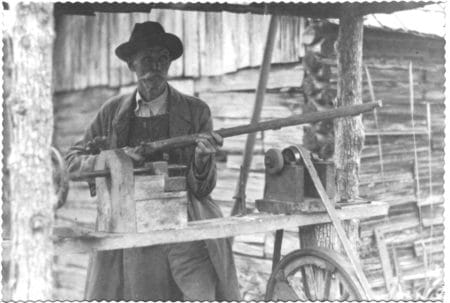

The Whitleys’ grandson James was born in the cabin in 1873 and lived there until 1961, with the historic deer-killing gun hanging over the fireplace all of those years. From time to time, his rural life and old-school ways got him press attention. Then along came the Georgia Department of Transportation, seeking to eminent-domain the family land for the new I-285 freeway. Whitely is said to have offered the cabin and the historic Buckhead firearm to GDOT in exchange for sparing at least part of the property or building him a new home.

GDOT was not interested in saving the land – or owning a deer-slaying artifact — and set Whitley up in a Smyrna-area house instead. According to Beach, Whitley continued to favor a rustic lifestyle, including cooking in the fireplace of his new modern home. Whitley died the following year.

But the cabin and its contents, including the Buckhead Gun, survived. A friend of Whitley’s paid to have the cabin moved – lock, stock and smoking barrel – to the back yard of his Buckhead home. Whitley never lived there again, but the cabin remains to this day, hidden from public view.

This private preservation resulted in some personal complexities and sensitivities that leads the Heritage Society to keep those involved anonymous, at least for now. The cabin is not available for viewing, and for public consumption, Beach will only say that an heir currently owns the supposed Buckhead Gun.

That heir has loaned the firearm to the Heritage Society for research and display during its April 28 “Mansions, Gardens and Ghosts” bus tour of historical sites.

For now, Beach is something of a one-man Warren Commission on the killing of the Buckhead buck. He’s got a sheaf of newspaper clippings and many historic photos of the cabin and the weapon. The firearm itself has one solid research lead: a maker’s mark on the barrel from H.E. Leman, a famed gunsmith from Lancaster, Pa., whose work can be traced in two speciality museums.

One early opinion is that the firearm – estimated to be roughly .36-caliber — had some alterations to its stock and a possible conversion from a flintlock to a caplock firing mechanism, but is substantially intact. And it might even still be capable of firing. But Beach says that there won’t be any test hunting of local deer. In the Buckhead that grew up around Irby’s store, deer-hunting is now illegal.

“We now protect the deer that they looked at as their dinner,” says Beach.