In February 1865, as Union troops lowered thousands of artillery rounds, weapons and other Confederate ammunition into the Congaree River, an explosion erupted.

It was the day after one-third of Columbia was destroyed by fires amid the Union soldiers’ siege of the city near the end of the U.S. Civil War.

Union troops were recklessly throwing munitions into the river, one general recalled, and as a result, one percussion shell struck another and ignited.

The blast instantly killed four soldiers, and another later died from his wounds. Twenty-one other soldiers were injured, and multiple wagons carrying the ordnance were destroyed.

Over 150 years later, Dominion Energy contractors unearthed what is believed to be a piece of one of those wagons from the Congaree River. It was one of the hundreds of Civil War artifacts recently pulled out of the river amid a cleanup of toxic tar.

Confederate artillery rounds ranging from the size of golf balls to bowling balls were pulled out of the Congaree River. Sean Norris/Provided

Cannonballs varying from the size of a golf ball to a bowling ball, musket ammunition and a Confederate sword marked “B. Douglas & Co. Columbia, SC” were also recovered.

Such finds aren’t unusual in the Congaree as it passes through Columbia. Residents, mayors and collectors have been pulling out Confederate bombs, ammunition and other war materials from the waters since at least 1930, and likely earlier.

Interviews with historians and anthropologists, newspaper archives and records kept by the University of South Carolina detail the story behind how the ammunition ended up there, where the rest could be and the many excavations that have taken place since that winter morning in 1865.

Disposing of ordnance

As Gen. William T. Sherman’s army campaigned from Atlanta to Savannah, his troops eventually made their way north to the Carolinas as part of a plan to meet up with Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's forces in Richmond, Va.

Other than a few skirmishes, Union soldiers met little resistance as they approached Columbia, which had become an important railroad center and munitions depot for the Confederacy, as well as the capital city of the first state to secede.

“Columbia was a very substantial Confederate weapons site,” University of South Carolina Civil War historian Thomas Brown said. “(The Union) wanted to destroy those facilities.”

In the early morning of Feb. 16, Confederate soldiers burned the Gervais Street bridge as a delaying action, then fled the city.

That night, a Union brigade of roughly 15,000 soldiers crossed the Congaree River from the Lexington County side, using a makeshift bridge. The mayor of Columbia approached a brigade official and surrendered the city.

On Feb. 17, multiple fires broke out within the city. Bales of cotton stacked throughout the streets of Columbia caught fire, destroying one-third of the city before fire brigades and Union soldiers could contain the blaze.

The next day, Union soldiers secured the city and carried out Sherman’s General Order No. 26, which instructed soldiers to destroy public buildings, railroad property and manufacturing and machine shops.

A report from a Union general and Sherman’s personal memoirs indicate that on Feb. 18 and 19, a group of soldiers destroyed the state arsenal, which included “shot, shell and ammunition.”

Among the destroyed Confederate munitions: more than 10,000 muskets and rifles, 6,000 barrels and stocks, 1.2 million rounds of ammunition, 100,000 percussion caps, 3,000 cutlasses and sabers, among other munitions.

“These were hauled in wagons to the Saluda River … and emptied into deep water,” Sherman’s personal memoir reads.

Civil War artifacts were discovered as Dominion Energy workers removed toxic tar from the Congaree River. Dominion Energy/Provided

According to Sean Norris, the lead anthropologist on the latest river cleanup, Sherman’s mention of the Saluda River — and not the Congaree, where artifacts have been repeatedly recovered — presented two possibilities.

One theory was that the Confederate ammunition was dumped in several locations, including the foot of Senate Street just south of the Gervais Street Bridge and another location upstream in the Saluda as Sherman indicated, though the second site remains undiscovered.

This was plausible, not just because of Sherman’s account, but also because federal troops recorded disposing of several munitions that have not yet been found.

An inventory listing what was captured by Union soldiers during the capture of Columbia in February 1865. Sean Norris/Provided

Those undiscovered materials include thousands of muskets, sabers, an anvil and other Confederate war items.

But according to Norris, it’s more likely that Sherman or the soldiers who reported to him simply confused the two rivers and that no ordnance was ever dumped at a second site.

The Union brigade camped near the Saluda river and crossed it near where the Riverbanks Zoo is today.

“You could potentially get confused on how many creeks you cross and where the confluences are and how it changes into the Congaree,” Norris said. “It doesn’t seem too likely that anything was dumped into the Saluda.”

It’s possible that the Union troops took some of the Confederate ammunition for the federal troops' own use or disposed of other ordnance in an undiscovered location away from the rivers.

A letter describing federal troops bending musket barrels and then disposing of them in a pit at an undefined location supports that conclusion, Norris said.

Although varying accounts describe the deaths from the accidental explosion — ranging from just four to 200 — a report from a Union general describes the event as follows:

On Feb. 19, 1865, about 1,200 Union soldiers were destroying ordnance stores by throwing it into a nearby river in a reckless manner. Four soldiers, all of them volunteers from Illinois, were instantly killed by an explosion. Another later died from his injuries.

Work being completed in the Congaree River. Matthew Long/Dominion Energy/Provided

Those deaths, along with two other Union soldiers who were shot and killed by Union authorities during a riot in the city, were the only casualties during the Union siege of Columbia.

The diary of 17-year-old Columbia resident Emma LeConte reported a large explosion shaking her home on Feb. 19.

Norris said that the burned wagon wheel hub was one of the most remarkable finds. It doesn’t necessarily teach historians anything new about what happened, but it does give physical credence to what has up until this point only been observed in historical records.

Excavations

A burned Columbia behind them, Union troops continued their campaign north through the Carolinas, leaving Columbia on Feb. 20. In a few months, all remaining Confederate forces would surrender, ending the four-year war.

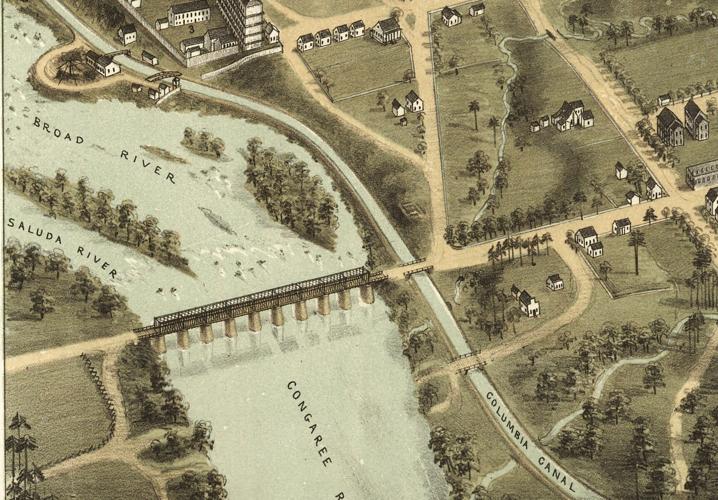

Columbia residents likely began taking dumped munitions from the river immediately, Norris said. A map of Columbia in 1872 shows that the area just south of the Gervais Street Bridge would have been easy to access.

A cropped map of Columbia in 1872 shows the area just south of the Gervais Street Bridge, where Confederate ammunition was dumped into the river by Union soldiers in February 1865. Library of Congress/Provided

In a 1929 memoir titled "Old and New Columbia," author J.F. Williams wrote that he and his friends would dive and retrieve cannon balls and shells in the river.

A year later, a local newspaper reported that two fishermen found Civil War ammunition in the Congaree, a discovery that motivated New Brookland Mayor L. Hall and a city councilman to purchase the artifacts and organize efforts to recover the remaining munitions.

The recovery project took place “above the Senate Street frontage on the river.” Workers pulled out a collection of 1,945 artifacts.

The two men halted their excavation efforts, thinking they had retrieved “practically all of the lost ammunition.”

In June 1930, “several thousand pounds” of the recovered ammunition were put on display at 1615 Main St.

Residents paid a fee to view the display, and proceeds went to the United Daughters of the Confederacy chapter of Columbia, a group that historically has promoted the Lost Cause ideology and worked to erect and sustain Confederate monuments across the U.S.

Where those recovered artifacts ended up is unknown, Norris said.

In May 1938, the Spartanburg Herald reported that two New Brookland high school boys, Luther J. Morris and Knowiton Jeffcoat, found a 2.5-foot unexploded artillery projectile in the Congaree, weighing about 100 pounds.

The two boys attempted to melt lead out of the round by tossing it in a bonfire, which caused an explosion that sent steel fragments flying, narrowly missing the 18-year-olds.

The headline by The Spartanburg Herald read, “Youngsters try to melt lead from old war shells: Explosion almost reopens Confederate conflict.”

“The Confederate war was over 73 years ago, but the delayed explosion of one of its shells almost added two casualties this week,” the story read.

The most recent recovery, which began in 2015 with most of the artifact discoveries taking place this year, used armor-plated excavators, sonar equipment and bomb-disposal experts to protect workers from unexploded ordnance.

One artillery shell that may have had some gunpowder left in it was sent to Shaw Air Force Base, Dominion Energy South Carolina President Keller Kissam said at a Nov. 16 press conference.

Additional, but smaller, excavations were conducted in the early 1980s, pulling out similar items.

In 2008, a 10-inch cannonball listed as having been pulled from the Congaree River was advertised on Live Auction World for $675.

Collectors and others interested in searching for buried material must first obtain a license through the University of South Carolina's S.C. Institute for Archeology and Anthropology .

Artifacts found in the Congaree River. Sean Norris/Provided

What remains

According to Norris, nearly all of the ordnance has now been removed from the river. Some materials, which remain unaccounted for, could have been destroyed elsewhere, brought to other states by Union soldiers or be sitting deep beneath layers of sediment in the Congaree.

The recovered artifacts, the most notable of which are the Confederate saber and the wagon wheel hub, will undergo an 18-month preservation process.

“They were in pretty good condition,” said James Spirek, USC underwater archaeologist. “There’s a little bit of rust that needs some treatment. Once they’re cleaned up … they’re gonna be some real nice artifacts to display.”

They will likely then make their way to the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum.

The museum’s director, Allen Roberson, said part of his budget request this year will include plans to renovate a small gallery to include a 15-foot floor-to-ceiling display.

The new artifacts could be displayed there if the funding is secured.

Thousands of non-Civil War artifacts were discovered during the most recent excavation as well, including pre-contact Native American artifacts and thousands of items related to the history of Columbia, including a large anchor thought to be from one of the steamships that traveled the river in the late 1800s to early 1900s.

Brown said the burning of Columbia is a signature event for the city.

“This recent discovery promises that the story will continue to be told locally,” he said. “It's important to keep in mind that part of the story is, when the city is largely destroyed, the city is quickly rebuilt, but it's rebuilt in a whole different environment, a post-emancipation environment, and that part of the story is also super important.”